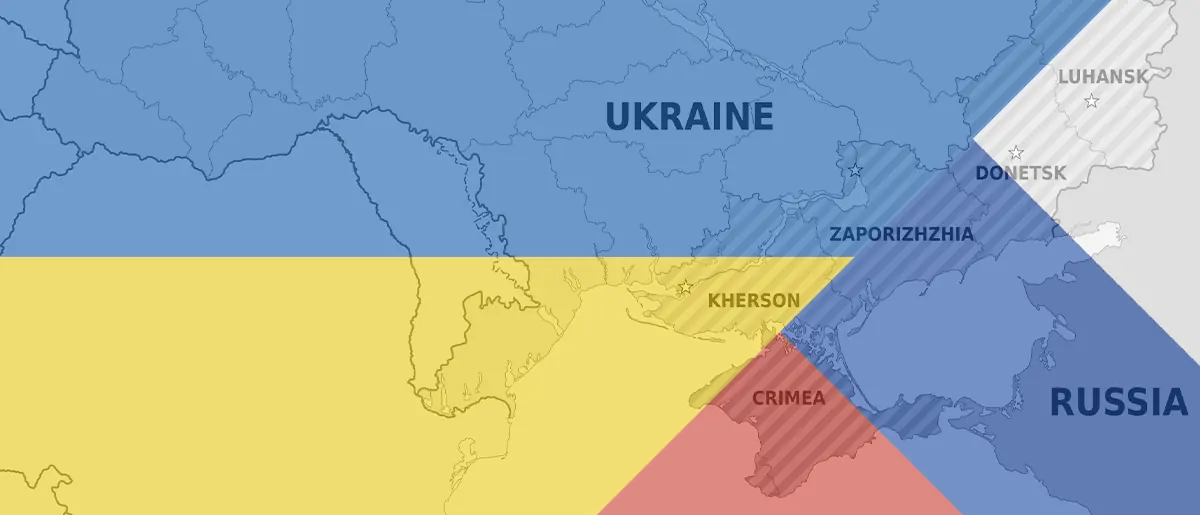

The modern conflict between Russia and Ukraine started in February 2014 with the Russian annexation of Crimea and the Ukrainian civil war in the Donbas region—the oblasts (provinces) of Donetsk and Luhansk. It developed into a full-blown war when Russia invaded Ukraine, including areas far beyond the Donbas, in February 2022. This conflict is rooted in centuries of history, and a post about that is coming soon . . . but, in short, the situation is more complex and nuanced than most casual observers assume. It is not as simple as screaming, “Ukraine good, Russia bad!”

Russian President Vladimir Putin (United Russia) is the aggressor; this is clear. He wants to reclaim Russia’s (or the Soviet Union’s) past glories and is now fully committed to totalitarian jingoism and self-sure belligerence. That does not mean that Russia is entirely in the wrong; it has legitimate grievances, especially about its deep historical, cultural, moral, and practical claims to the Crimean Peninsula. Acknowledging this does not make me a Putin puppet or apologist.

Even when there are clear “good guys” (Ukraine) and “bad guys” (Russia), it is rare that the good guys are 100% good or the bad guys are 100% bad. And anyway, we must look at the situation pragmatically. Good guy or bad, right or wrong, what matters now is ending the war in a way that everybody can live with.

Possible Ends

There are three possible ways the war between Russia and Ukraine can end:

- Ukraine wins outright: Russia is forced back to its pre-war borders and stops fighting. Crimea, the Donbas region, and the other disputed territories all go back to Ukraine. This is what Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy (Servant of the People) wants, and what Ukraine’s allies like the United States have advocated, but the odds of it happening are practically zero. The only way to increase the odds would be for Ukraine’s allies, including the U.S., to enter the war . . . which could just as easily turn this into World War III.

- Russia wins outright: Ukraine reaches the point where it cannot hold out any longer and surrenders. Russia walks away with whatever territory they hold when the last Ukrainian soldier lays down his arms . . . which could be anything between their current holdings in eastern Ukraine and the whole country. The odds of this happening are probably something like thirty-five percent.

- A negotiated peace: The leaders of the belligerent states decide that coming to some kind of agreement is preferable to prolonging the war. This can only happen when both sides are willing to make concessions . . . they accept they won’t get everything they want because the enemy won’t either. This is the most likely outcome; it has always been. The odds are somewhere around sixty-five percent.

This is reality.

You and I (and President Zelenskyy) wish Ukraine could defeat Russia and restore its pre-war borders, but that is not going to happen. In a perfect world, Putin’s Russia would gain nothing from its idiotic war of aggression, but this is not a perfect world. Diplomacy, as the old saying goes, is the “art of the possible.”

Barring a radical change in Russian policy—which is possible, but still unlikely, only if Putin dies, resigns, or is deposed—the only way to put an outright Ukraine win on the table is to make a dangerous escalation. The U.S. could do the very thing we have been trying to avoid since World War II: fight Russia head-on. If we survive, Ukraine might too. But it could also turn the planet into a nuclear wasteland. That would be bad.

The best achievable outcome that doesn’t involve an unacceptable risk of nuclear destruction is a negotiated peace. For that to happen, Ukraine must accept something less than total victory. If the demand for a return to Ukraine’s pre-war borders is non-negotiable, Russia has no reason to talk.

Trump’s Play

When Russia took Crimea in 2014, world leaders—including President Barack Obama (D)—sent the diplomatic equivalent of some strongly-worded letters to Putin. They said they stood with Ukraine and imposed some sanctions, but that was about it. There was little substantive action. When the conflict expanded to the Donbas region—the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (provinces)—nothing changed. After Russian troops or pro-Russian separatists shot down Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17, apparently thinking it was a Ukrainian transport, we issued a flurry of even more strongly-worded letters and slightly stronger sanctions

During President Donald Trump’s (R) first term, the situation between Russia and Ukraine did not improve, but also did not noticeably deteriorate. The breakaway de facto states of Donetsk and Luhansk and their Russian supporters avoided escalation, though no cease-fire agreement held longer than two weeks at a time. And in 2019, Ukraine elected Zelenskyy president in part because he promised to end the war in Donbas.

When President Joe Biden (D) took office in 2021, Putin almost immediately set Russia on its course toward invasion . . . probably because he expected Biden to respond as impotently as Obama had. When the invasion did occur, the U.S. and others imposed stronger sanctions on Russia than Putin probably expected, and, after initial hesitance, dumped a mind boggling amount of money and weapons into Ukraine. For the rest of Biden’s term in office, he voiced unwavering support for Ukraine and demanded that Russia retreat to the pre-war borders.

This is a fine, principled position to take . . . but by aligning the U.S. entirely with Ukraine, Biden abdicated any role we might have had in brokering a peace. From Russia’s perspective, we were aligned with the “enemy,” so why would they trust us? Why even talk to us?

Now that Trump has returned to office, he and his administration are trying to break the stalemate and find a resolution. This requires getting Russia to the negotiating table. We must undo Biden’s work to position us in lockstep with Zelenskyy—and with Zelenskyy’s demands for a full Russian withdrawal. Trump must convince Putin that we can be a neutral broker for peace, and, at the same time, convince Zelenskyy that we aren’t going to keep dumping hundreds of billions of dollars into a war he cannot win. Then we can start a real negotiation.

The recent embarrassing spectacle at the White House where Trump berated Zelenskyy generated plenty of breathless doom-and-gloom headlines, but it was not a random, unnecessary act. It was a strategic move to change the dynamic and lay the groundwork for future negotiations. Trump was signaling to Zelenskyy that we will not keep handing him blank checks, and, more importantly, Trump was showing Putin that we can be a “fair” broker and are not in Zelenskyy’s pocket. It is no coincidence that Russian TASS reporters were at the White House that day; they were invited to make sure Putin got the message.

Most presidents would have done all this in private meetings with Zelenskyy and through back-channel communication with Putin. Trump is a ‘bull in a china shop’ and accomplished the same thing in a fraction of the time with the news cameras rolling. It looks bad, and bolsters the still-baseless opposition view that Trump is a Russian asset . . . but it also puts us in a better position to achieve the desired outcome: a negotiated peace where Ukraine still exists and Russia has no reason to bother them anymore.

Proposed Solution

What might a negotiated peace look like? Here is what I propose:

- First point: Immediately cease fighting and begin a military withdrawal.

- All Russian and Ukrainian forces shall stand-down to defensive positions and engage in no armed conflict unless attacked.

- Russian forces shall begin withdrawing from occupied territories within the de jure borders of Ukraine, except Crimea and Sevastopol, and complete the withdrawal within thirty days.

- Ukrainian forces shall begin withdrawing from occupied territories within the de jure borders of Russia, and from the disputed territories of Crimea, Sevastopol, Donetsk, and Luhansk, and complete the withdrawal within thirty days.

- Ukrainian forces in the Kherson and Zaporizhia oblasts shall not advance from their current positions as the Russian occupation forces withdraw.

- Second point: Establish an international peacekeeping force.

- An international force composed of a voluntary coalition of states shall be established to maintain peace and enforce this agreement.

- This force shall be deployed to Donetsk, Luhansk, and portions of Kherson and Zaporizhia previously occupied by Russia before the completion of the thirty-day withdrawal and remain until the dates defined in this agreement.

- Two states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), excluding the United States, shall be appointed by that organization to participate in the peacekeeping force.

- Two states of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), excluding Russia and Belarus, shall be appointed by that organization to participate in the peacekeeping force.

- Other nations may participate in the peacekeeping force only by mutual agreement between Russia and Ukraine.

- Third point: Crimea, including Sevastopol, will remain Russian; Ukraine must be remunerated.

- Ukraine shall acknowledge that Russia’s intervention in Crimea in 2014 was in response to political instability and a coup in Ukraine, and at the request of the government of the former Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

- Russia shall acknowledge violation of previous agreements relating to Crimea and pay appropriate monetary reparations to Ukraine for its loss of territory, loss of access to the Sevastopol naval base, and the Crimean portion of war expenses.

- Ukraine shall acknowledge Russia’s historic claim to Crimea, accept the Republic of Crimea’s assertion of independence and request for Russian annexation, and, upon payment of the agreed-upon remuneration, renounce all claims to Crimea and Sevastopol.

- Fourth point: Ukraine will remain a free and independent state.

- Russia shall permanently recognize the independence and legitimacy of Ukraine, end all interference in Ukrainian affairs, and renounce all claims to Ukrainian territory except as described in this agreement.

- Russia shall renounce all claims to the oblasts of Kherson and Zaporizhia. The international peacekeeping force shall withdraw from these oblasts after one year and return them to unrestricted Ukrainian governance.

- Ukraine shall guarantee it will be governed as a constitutional republic, and acknowledge that any coup or other violation of constitutional order will invalidate this agreement and lead to possible foreign intervention and occupation.

- Ukraine shall not be considered for European Union or NATO membership for fifteen years. If Ukraine chooses, with the assent of its people, to join one or both organizations at that time, Russia shall take no military action.

- Fifth point: Self-determination in the Donbas.

- The oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk shall be occupied by the international peacekeeping force for a period of five years, and no Ukrainian or Russian military activity shall occur in either oblast during that time.

- During the five-year occupation period, Ukraine shall be acknowledged as sovereign and shall manage the civil affairs of the oblasts as it does in all its others, including appropriate investment in public infrastructure and government services.

- At the conclusion of five years, the international peacekeeping force shall organize free and fair referendums, and the people of the oblasts shall choose to remain with Ukraine or join Russia. Ukraine and Russia shall unequivocally accept the results of the referendums.

- In oblasts where Ukraine wins the referendum, Russia shall cede all claims and permanently accept Ukrainian sovereignty there.

- In oblasts where Russia wins the referendum, Russia shall pay an appropriate remuneration to Ukraine for the loss of territory and war costs relating to that oblast. Ukraine, upon payment, shall cede all claims and accept Russian sovereignty there.

- Sixth point: The United States shall enforce this agreement.

- Any future aggression by Russia or Ukraine in violation of this agreement shall be treated as an act of war against the United States of America and shall trigger a full-scale military response.

All-in-all, this would be a reasonably fair resolution.

Russia would get Crimea (at a cost) and guarantees from Ukraine and the international community that Ukraine will not be joining NATO or the E.U. any time soon. Ukraine would get an end to the fighting, its own guarantees for defense, and keep the two disputed oblasts it has the strongest claim to (Kherson and Zaporizhia). Both sides have the chance to win Donetsk, Luhansk, or both; there, Russia has the advantage of likely public support, but that is mitigated by Ukraine controlling those regions in the short-term and having the chance to change minds. If Ukraine loses them anyway, it at least gets paid for its troubles . . . and knows it lost the territory to democracy, not violence.

For any of this to work, both Ukraine and Russia need to believe that the United States and other world powers will intervene if either of them violates the terms. These countries made agreements before, and Russia broke them. Putin believed—correctly, it turns out—that the world powers weren’t going to put themselves on the line to stop him.

That will be the next big challenge. Trump’s play might get the parties to the table, but we must somehow make them both believe that the United States will use its full military might to stop future violations. Without that, any peace agreement will be written in the same loose sand as the last one.