Photography is one of my main hobbies. Of course I take most of my pictures with my phone now—just like everybody else—but when I want to do some serious shooting, I use cameras and lenses in the Sony E-mount mirrorless system.

One of the nice things about mirrorless cameras is that they have a much shorter flange focal distance than their single-lens-reflex (SLR) predecessors. The practical benefit is you can get equivalent optics in much smaller, lighter camera bodies and lenses. A secondary benefit for hobbyists and enthusiasts is that you can use all sorts of cool vintage lenses. Almost any SLR lens with manual controls can be adapted and used on a mirrorless body. Just grab an adapter from Fotodiox or one of its competitors and you’re good-to-go.

This can be a big money-saver if you’re strategic about it. For example, I wanted a macro lens for close-up work, but I don’t do enough of it to warrant spending a lot of money. Sony’s 50mm ƒ/2.8 full-frame macro lens retails for $549.99, and third-party options from companies like AstrHori, Samyang, Tokina, and TTArtisan still run between about $250 and $400. But I didn’t need something new . . . any decent macro lens with good glass would work.

So I poked around on eBay and found a used Nippon Kōgaku (Nikon) Micro-Nikkor 55mm ƒ/3.5 from 1966 that was in great condition and had an original M2 extension tube. The whole kit—including taxes, shipping, and the Fotodiox mount adapter—cost less than $124.09. That’s a 77% discount from Sony’s first-party option, but I got something that looks cooler and still does what I need it to do.

But today I want to tell you about a very different lens. Come with me on a completely pointless journey into an obscure, forgotten, and mostly-irrelevant corner of the history of consumer photography.

Jump to the Summary of Findings

While I was closing the last few gaps in my lens collection with some vintage glass (including the aforementioned Nikon macro), I happened upon a lens I just couldn’t resist. It was on sale for less than $30. Of course I’d need to buy a Fotodiox adapter for the Pentax K-mount, which would cost almost as much as the lens itself . . . but it was still worth it. I’d like to introduce you to my JCPenney 135mm ƒ/2.8 telephoto prime:

Shot on Apple iPhone 14 Pro

There’s a Sale at Penney’s! – Johnny

As you may (or may not) know, JCPenney was (is?) an American department store chain. In 1898, the eponymous James Cash Penney went to work for Thomas Callahan and Guy Johnson, who owned a chain of Golden Rule dry-goods stores in Colorado and Wyoming. Penney later joined the partnership, and in 1902 he opened his own Golden Rule store in Kemmerer, Wyoming—JCPenney’s “mother store.” When Callahan and Johnson dissolved their partnership in 1907, Penney bought the three Golden Rule stores he had opened, consolidated them under the “J. C. Penney Company” name, and began a rapid expansion.

The company had over five-hundred stores in 1924, and doubled that number in the four years that followed. It opened its first “full line” mall department store in 1961. By the late 1970s, JCPenney—often just called “Penney’s”—was one of the main big-box “anchor” retailers at most American shopping malls.

In their heyday, you could get pretty much anything at the big department stores, or mail-order it from their massive printed catalogs. JCPenney, Sears, and Montgomery Ward were a big deal. They devolved into the unremarkable clothing and home-goods stores you remember from the 1990s, then withered under the onslaught of Walmart, Target, and, finally, Amazon. Montgomery Ward went out of business in 2001, but Sears and JCPenney are still operating (sort-of). You can sometimes find them hanging on for dear life in the post-apocalyptic wasteland of your local mall. Sears allegedly still has nine stores in the United States. JCPenney somehow has more than six-hundred.

The department stores often sold generic, store-brand, and private-label goods as lower priced alternatives to the big brands, much like Walmart and Amazon still do (think “Great Value” and “Amazon Basics”). These were made by outside firms under contract. Their camera departments had a selection of cameras and lenses from the big names—Kodak, Nikon, Pentax, and more—but also some cheaper stuff under their respective house brands. Sears sold a wide variety of camera products as “Sears,” “Tower,” and “Marvel.” Montgomery Ward sold cameras as “Wards.” JCPenney was also putting their name on camera gear, but there is comparatively little information about them online.

The Investigation Begins

I wanted to find out what company really manufactured this JCPenney lens.

The first big clue is that it is marked, “made in Korea.” It’s safe to assume that means South Korea, not the “hermit kingdom” to its north. The most well-known South Korean lens company—LK Samyang—made “white label” lenses for other brands before it became successful under its own name, so it was an obvious suspect. I have several Samyang lenses in my collection, including three automatic primes (24mm ƒ/2.8; 45mm ƒ/1.8; 75mm ƒ/1.8) and a manual wide-angle prime (14mm ƒ/2.8). It would be cool if this goofy vintage lens was their distant ancestor.

I found many online discussions about South Korean 135mm primes from the 1980s, and they mostly ended with somebody saying something like, “Well, it looks like a Samyang to me, so it’s probably one of theirs.” But there were other white-label lens makers in South Korea at the time, including spinoffs from established second- and third-tier Japanese firms. JCPenney, Sears, and others had sourced similar lenses from Japanese companies in the 1970s and 80s, and one of them might have kept making the same lens through a South Korean division to reduce costs. I wanted something more definitive.

I sent an email to Samyang’s U.S. division, gave them some photos, and asked if it was one of theirs. To my happy surprise, they answered promptly . . . but the answer they gave was disappointing: “I can confirm that this is not a Samyang lens. Unfortunately, that is all the information we have about this lens.”

I sent a message on Twitter (now X) to the current incarnation of JCPenney, and they told me, “Sadly, we not have any information on the item. We wish you the best of luck finding the answer to your question. Thank you for being a valued JCPenney customer. Have a great day!” You too, zombie retailer!

I started scouring the web for other leads, which took me down all kinds of “rabbit-holes” and false paths. There are tens—or hundreds—of similar 135m ƒ/2.8 lenses from multiple companies and brands with varying amounts of documentation. Most of them were made in Japan, but there are multiple South Korean versions too. The chatter about this specific lens—the one that was made in South Korea, has 52mm filter threads, has an integrated hood, and has a matching depth-of-field scale—kept pointing in the general direction of Samyang, but there was no proof.

I sent an email to Samyang’s main South Korean office for a second opinion (because I was suspicious of the U.S. division’s quick denial). No answer.

I sent another to the Korea Camera Museum. No answer from them either.

To the Catalogs!

I went back to the lens itself to see if I could develop any new leads.

I didn’t disassemble it to search for hidden markings, but on the exterior it had a serial number and a product code. The first two digits of the serial—85—probably indicated that the lens was made in 1985. JCPenney often prefixed the serial numbers on its house-brand products with a two-digit year code. The product number—624-4270—probably represents a three-digit manufacturer code followed by a model code. Unfortunately, I could not find any lists mapping JCPenney manufacturer codes to suppliers.

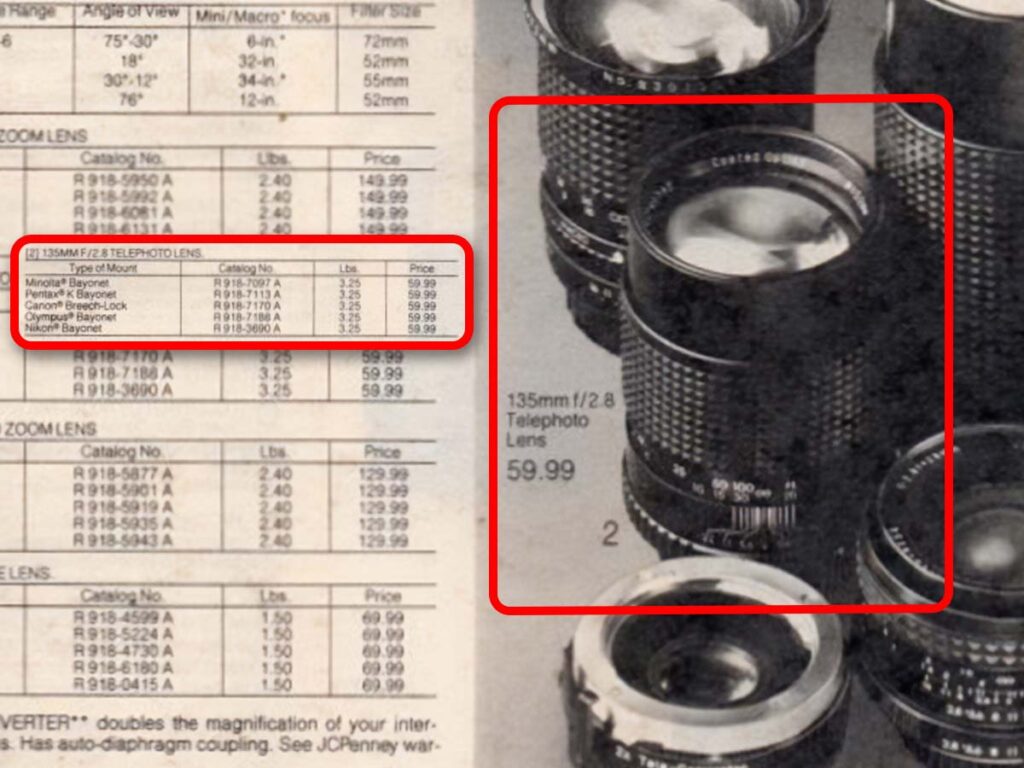

I went to Muse Technical’s “Catalogs & Wishbooks” archive to browse through digitized copies of old department store catalogs. Muse doesn’t have JCPenney’s 1985 seasonal catalogs, and the lens wasn’t in the company’s less expansive 1985 Christmas Book, but it was in the catalogs immediately before and after 1985. It’s on page 864 of the 1984 JCPenney Fall/Winter Catalog and page 583 of the 1986 JCPenney Spring/Summer Catalog.

The 1984 list price was $59.99 (about $183, inflation adjusted). The 1986 list price was “Priced down $20” to $49.99 (about $116, inflation adjusted). It was either $69.99 in 1985, or they didn’t know how to do math. JCPenney lenses came with a five-year warranty and were “imported from Japan or Korea.” Between the likely year code in the serial number, and evidence that the lens was being sold in the mid-1980s, it’s probably safe to say this lens was in-fact manufactured in 1985.

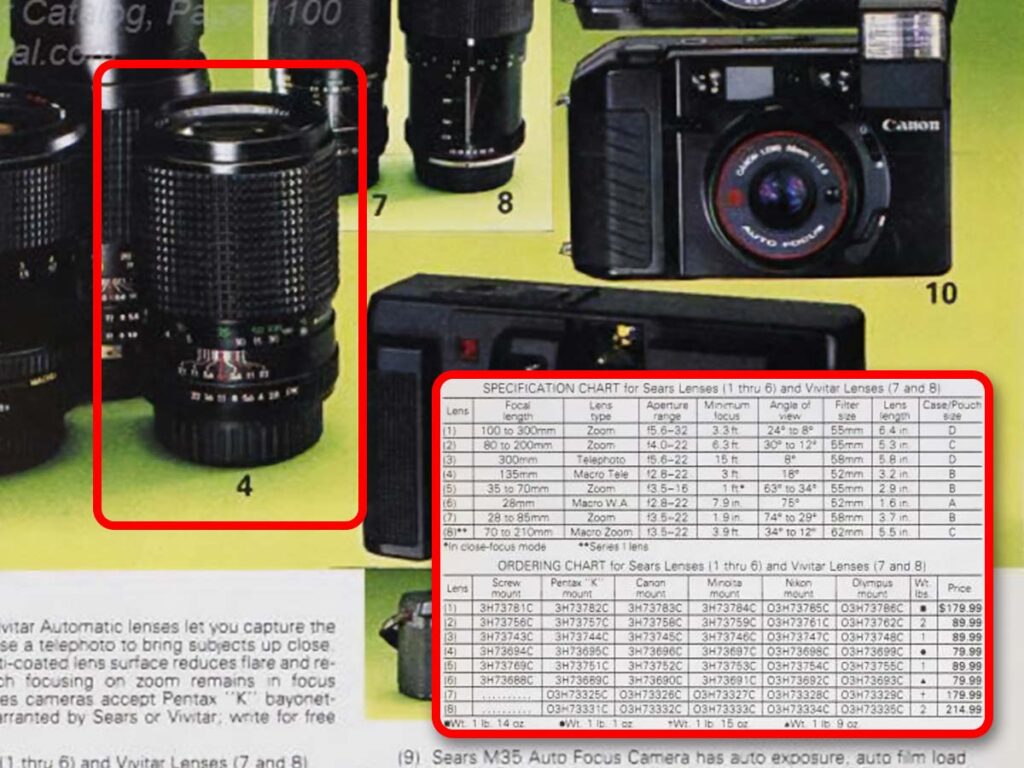

I knew the lens was also sold by Sears, so I took a look at their catalogs too. Sure enough, it’s on page 1,100 of the 1984 Sears Fall/Winter Catalog and page 918 of the 1985 Sears Spring/Summer Catalog. It is listed (but not shown) on page 1089 of the 1985 Sears Fall/Winter Catalog. Sears was selling them for $79.99 (about $245, inflation adjusted).

Catalog images from Muse Technical; call-outs and highlights added

The Sears Lead

There’s a lot of public information about products sold under the Sears brand and its various house-brands like Craftsman and Kenmore—much more than for JCPenney. Sears was the juggernaut; for a long time it was America’s number-one retailer.

The catalogs didn’t provide actual product numbers, just catalog or ordering numbers, but it was pretty easy to find photos of the Sears-branded version online (example #1, #2, and #3) including their serial numbers and product codes. Sears product codes, much like JCPenney’s, were a three- or four-digit manufacturer prefix followed by a separator and a model number. These lenses all had the manufacturer prefix 202. According to the Sears and Craftsman manufacturer list, supplier #202 is “Gannon Mfg.”

Well . . . that isn’t right. Gannon Manufacturing, which is now part of Woods Equipment, was an American company that made snow removal equipment. It built Craftsman-branded snow blowers and plows.

I briefly suspected Gannon of importing and reselling South Korean lenses as a side-business, but I found no evidence for that. More likely, the Sears supplier lists you can find on the Internet are for Craftsman, Kenmore, and maybe other Sears divisions, but do not apply to the camera department, which either had its own system or was part of a division of the company that managed these things independently. This was another investigative dead-end.

Next, I decided to see if I could find an example of the lens with the manufacturer’s “first-party” brand on it. Plenty of companies sold similar or identical products under multiple brands, including their own. For example, Sears Tele-Games Pong home gaming systems were made by Atari and were functionally identical to Atari’s own Pong games. I spent an inordinate amount of time on eBay, camera forums, and image-search tools looking for this particular 135mm ƒ/2.8 lens in a sea of other 135mm ƒ/2.8 lenses. I found . . . many.

Brand names that companies slapped on this lens included Albinar, Aqunon, Chinon, Imado, Praktika, Prospec, Revuenon, and Star-D. There is little or no information about who was making lenses under these names in the mid-80s. These were mostly small, niche retailers and resellers that popped up, sold some re-branded stuff, and promptly disappeared into the mists of history . . . or were venerable old names that used to be serious camera companies but turned into second-rate resellers as they slid into bankruptcy.

But, finally, I found another promising lead. Copies of the lens had another relatively well-known brand name on them: “Vivitar.”

The Vivitar Lead

Ponder & Best was founded by Max Ponder and John Best in the Los Angeles, California, area in 1938 to import and distribute photography equipment. In their early days they imported products from well-known German camera brands, but, after World War II, shifted to working mostly with Japanese companies. Ponder & Best was responsible for introducing brands like Mamiya and Olympus to the U.S. market. In the 1960s, the company created their own brand—Vivitar—and commissioned Japanese companies like Kino Precision to make lenses for them.

Some of Vivitar’s products were pretty good for the price. Some weren’t, especially in their later days. The company still exists . . . sort-of . . . in a zombie form not unlike Sears or JCPenney.

Like the department stores, Vivitar did not make anything themselves. They sold a surprising variety of 135mm ƒ/2.8 prime lenses over the years, which mostly came from Japanese suppliers, but the mystery Korean lens was in the mix too (example #1, #2, and #3). Because Vivitar is well-known and sold some lenses that are well-liked by enthusiasts, there is information about Vivitar serial numbers and suppliers out there. It’s not verified information, but it seems legit.

Their system between about 1970 and 1990 was a one- or two-digit manufacturer code followed by a single digit representing the year of manufacture (you have to guess the decade from context clues). Next came two digits representing the week of manufacture, although, given the code length on these lenses, I suspect this was sometimes omitted. The remaining numbers were the unique, sequential serial number.

In the three examples I linked to above, assuming the documentation is right about what the first three digits mean, we had serial prefixes 813 (manufacturer #81, made in 1983), 815 (manufacturer #81, made in 1985), and 899 (manufacturer #89, made in 1989). Since my lens was made in 1985, the most likely manufacturer is the one coded by Vivitar as #81 . . . which is convenient, because the manufacturer list doesn’t include #89. (I have a theory about that; we’ll come back to it later.)

Who was Vivitar manufacturer #81? It was . . . ”Polar.”

Who the heck is Polar?

Finding Polar

There is little information on the Internet about any camera or lens company called Polar. Here and there in the camera forums you’ll find passing mentions of “Polar” or “Auto-Polar” lenses—mostly from people who find them at flea markets, estate sales, or auction lots—but few were sharing any photos or details.

The most helpful information I found was in a 2020 thread on Pentax Forums. User “wingman” (Mark from Tampa Bay, Florida) said he “bought a camera lot” with two Polar lenses in the bag, but couldn’t find any information about them. User “UMC” (anonymous from Vienna, Austria) responded:

The brand name Polar is a bit of a mystery to me.

Nowadays it is being used as one of the many brands of the contemporary Samyang lens line. At least I know that the Samyang 85mm 1.4 exists with a “Polar” label on.

Presumably in the 80ies Polar seems to have been a store or sales brand for ‘cheapo’ OEM lenses from the likes of early Samyang. I assume that it must have been particularly popular in Italy or even a brand by an Italian distributor.

“UMC” went on to list a bunch of Polar lenses. He identified two 28mm ƒ/2.8 primes as “most likely Samyang,” an 18-28mm ƒ/4.0-4.5 zoom as “Samyang – it also exists as Beroflex, Cambron, Centon, Exakta, Goko, Maginon, Panagor, Phoenix/Samyang, Sakar, Samyang, Sears, Sirius, Tokura,” and, most interestingly, a 135mm ƒ/2.8 as “looks like Samyang.”

Samyang, Samyang, Samyang. It keeps coming back to Samyang.

I couldn’t find an example of the modern Samyang 85mm ƒ/1.4 being sold with Polar branding, or any other recent products under the name, or any clear connection to Italy. “UMC” seemed to know what he was talking about, but hadn’t offered evidence. It was starting to look like another dead end. This stupid lens was becoming my “white whale.” I wanted to know for certain who made it, but I just couldn’t tie all the strings together. Time went by. I worked on other things.

Finally it hit me: Trademarks.

If a company was going to be shipping lenses around the world and entering into distribution contracts while calling itself Polar, it was probably going to file for a trademark. Many national trademark databases are online now, and most of them participate in the the Global Brand Database of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). I went to the search page, entered “Polar” for the brand name and “camera” for the goods-and-services category, and clicked on the search button.

And there it was. Mystery (probably) solved.

A South Korean company submitted a trademark application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on November 6, 1984, stating that it intended to use the name “POLAR” in product areas “TELESCOPE, BINOCULARS, LENS, MICROSCOPE, CAMERA SLIDE PROJECTOR, DISTANCE METER, EXPOSURE METER, FLASH GUN[,] AND MOVIE CAMERA.”

The applicant’s name was “SAMYANG OPTICAL INDUSTRY CO., LTD.” of Masan, South Korea.

Almost There

According to the USPTO records for Samyang’s U.S. trademark application #73507512, it was examined and issued a “non-final action”—probably a rejection. The filer did not respond within six months, after which the application moved to the “abandoned” status. It appears that Samyang didn’t want to argue about it and just let the U.S. trademark die.

The application did refer to a preexisting foreign trademark in the Republic of Korea: Registration #85608 dated November 17, 1982. My initial searches for that trademark were unsuccessful, both at the WIPO Global Brand Database and at the Korean Intellectual Property Rights Information Service (KIPRIS). The reason was that the numbering system has been modified, and the records include a mix of Korean- and English-language characters. I did find it eventually by searching for “Polar” and filtering by date—it’s Korean trademark registration #4000856080000—note the bold digits; this number contains the one in USPTO records. (The KIPRIS system is temperamental, so if you click that link, good luck! It might load for you . . . eventually.)

The original applicant was listed as “SY Corporation Co., LTD,” which must have been Samyang’s legal corporate name at the time. All SY Corporation trademarks are now assigned to LK Samyang, so that adds up. They registered a bunch of names starting with “P” on the same day—“Palar,” “Polar,” “Polaris,” “Polaron,” and “Pallas.”

This is pretty solid evidence that Vivitar manufacturer #81—Polar—is, in fact, Samyang. And if that’s true, then Sears manufacturer #202 and JCPenney manufacturer #624 are Samyang too.

The problem is the unknown provenance of that Vivitar manufacturer list. It first appeared on Stephen Gandy’s CameraQuest, and Gandy said it came from “a former Vivitar executive.” The information seems legitimate, but it’s hard to know for sure. The authors of Camera-Wiki.org say, “No direct evidence to date confirms that Vivitar used the serial number system presented above,” and there are “likely still errors and omissions.”

Since #81 is allegedly Polar, and Polar is certainly Samyang (a South Korean company), and the #81 prefix appears on lenses that are labeled “Made in Korea,” it all lines up quite nicely . . . but it’s not quite proved “beyond a reasonable doubt.” So, the investigation continues.

More Evidence

I kept poking around on KIPRIS to see what other names Samyang was using back in the 1980s, just because of my persistent idle curiosity (or ADHD . . . or both). Those “P” names filed in 1981 were the earliest Samyang filings in the system. One year later, they filed for another set of trademarks: “Albinar,” “Super Albinar,” “Albinar ADG,” and “Photopia.”

Wait a minute . . . Albinar . . . that was one of those random brand names I found on the lens!

I went back and searched specifically for Albinar 135mm ƒ/2.8 lenses. There are a few variants, some of which don’t match, but there are plenty of examples of Albinar lenses that are identical to the lens we’re studying (example #1, #2, and #3). We don’t need to rely on a probably-correct-but-not-proved list of Vivitar supplier codes to link this lens to Samyang anymore.

This lens was sold—in volume—as an Albinar, and the Korean trademark filings make it clear that Samyang was using that name during the early-to-mid 1980s. There was an earlier European camera company using that name, but by the 80s it was mainly used as a store brand for camera gear sold in Best stores (see USPTO 73289697). It looks like “Albinar” lenses were made by Samyang in South Korea to be sold in the U.S. by Best Products.

A Third Argument

This lens was a Vivitar-branded product made by “Polar” and an Albinar-branded product sold by Best. We have pretty solid evidence linking the Polar and Albinar brands to Samyang. Between these two lines of argument, I think we can call it “proved beyond a reasonable doubt.” Regardless, I kept looking into it and eventually uncovered another bit of evidence.

In the January-March 1988 issue of Popular Photography, page 77, the editors wrote:

Samyang, one of the two major Korean lens makers, whose lenses had previously appeared only as Sears Roebuck optics, will now make their debut as QTII optics. (Although available in other countries under the Polar label, a Samyang spokesman explained that “Polar” was a bit too close to the name of a well-known U.S. maker of instant photography products.)

This is another bit of evidence that ties Samyang to both Sears and Polar—two brands that are linked to this lens. This may also explain why “Polar” did not work as a U.S. brand—it’s too similar to “Polaroid.” The authors of the quoted article were wrong when they asserted that Samyang lenses had “only” appeared under the Sears brand in the U.S., and that sort of error reduces its overall credibility, but, even so, it’s another piece of evidence linking Samyang to the Sears and Polar brands.

These three lines of evidence, when combined, are difficult to refute. My JCPenney 135mm ƒ/2.8 lens is almost certainly a Samyang lens . . . even if they don’t want to admit it.

Family Portraits

I got my Samyangs together for family portraits:

Shot on Sony α7 II with Sony FE 28-70mm ƒ/3.5-5.6

and Nippon Kōgaku (Nikon) Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/3.5

But . . . Why Polar?

Why was Samyang calling itself Polar in its dealings with Vivitar (and possibly other U.S. retailers)? I have a theory. This section is complete speculation; I have no inside information, and I’d love to be confirmed or corrected. Contact me if you know something.

Korean-made products were mostly unknown in the U.S. in the 1970s, but Japanese firms had been working hard to gain market- and mind-share here for decades. Plenty of U.S. consumers were buying Seiko watches, Nikon cameras, Sony headphones, Kenwood radios, and more . . . and they were starting to buy cars from Honda and Toyota too. South Korean companies, with encouragement from their government, wanted to emulate their Japanese peers and crack the American market.

Many of the big South Korean brands that are household names today first came to the U.S. in the late 1970s or 1980s. Samsung created its U.S. division in 1978. Goldstar Electronics opened a factory here—its first overseas factory—in 1982 (the company later became Lucky-Goldstar, which you may know as LG). Hyundai entered the U.S. automotive market in 1986. Kia entered the U.S. market indirectly with the 1988 Ford Festiva, which was a Mazda-designed car built by Kia under license.

According to Samyang’s company history, they were incorporated in 1972 as “Korea WAKO Co., Ltd.” (Now I’m wondering if it was connected to Japan’s Wako Co., Ltd., a department store spin-off from Seiko . . . another research project for another day.) They changed their name to “Samyang Optical Co., Ltd.” in 1979. By 1981, Samyang had been recognized by the Korean Foreign Trade Association as a “10 million Exporter Winner.” When they registered the “Polar” trademark in 1982, they were probably starting to push into to the U.S. market, and might have been starting to win some of those contracts with companies like JCPenney, Sears, Vivitar, and Best.

South Korean companies were looking to their Japanese peers as a template for success in America, and some Japanese companies used company names or brands that wouldn’t sound too “foreign” to American ears. Kasuga Radio Co. Ltd. called itself “Kenwood.” Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. went by “Panasonic.” Nikon is an abbreviated form of the company’s original name—Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (Japan Optical Industries Co., Ltd.)—that would evoke established western-style camera brands like Zeiss Ikon.

I suspect Samyang planned to use the Polar brand in the U.S. for similar reasons . . . but the USPTO rejected it, perhaps because it sounded too much like “Polaroid.” Samyang didn’t fight the rejection; they didn’t even respond. The stuff they were selling in the U.S. had other companies’ names on them anyway, and U.S. intellectual property law was probably relatively unfamiliar, so why bother?

Some time after the 1985 USPTO rejection, the company probably notified its American retailers and distributors that it wasn’t Polar anymore and should be called Samyang (or QTII, or something else). Vivitar might have decided to issue a new manufacturer code for its “new” supplier, which could explain why later Vivitar copies were marked #89 instead of #81. It all lines up pretty well.

That JCPenney Look

As for the lens itself . . . it’s nothing special. I bought it for “comic relief” in the first place. Nobody expects a forty-year-old JCPenney-branded telephoto to offer award-winning optics! But it’s fun to play around with . . . and it produces images that, to my eyes, have a certain “dreamy” quality you don’t get with modern lenses.

I’ve included some example photos below; I took them on my Sony α7 II in automatic mode (meaning, I set the aperture and focus manually on the lens and let the camera handle shutter speed and ISO by itself). These are unmodified shots; they went straight from the SD-card to Adobe Lightroom, and then straight out again through the exporter with no changes except to scale ’em down fro the web. I didn’t crop the images or make any other adjustments.

This is the same camera body with the same settings I used to take the “Samyang family portraits” earlier in the article . . . although the time of day and ambient lighting was different.

Shot on Sony α7 II with JCPenney (Samyang) 135mm ƒ/2.8

Summary of Findings

If you don’t want to read this lengthy-but-mildly-entertaining article, and just want to know who manufactured your 135mm ƒ/2.8 prime telephoto lens, well, here you go. Please review this “one-pager” summarizing the evidence: