On the evening of May 23, I decided to go for a relaxing drive in the country.

I do that sometimes . . . just because I enjoy driving. If I’ve had a stressful day or if I’m just craving some time behind the wheel, I’ll spend an hour or two aimlessly cruising the back-roads of Virginia. Although I live in South Riding, part of the suburban eastern half of Loudoun County, Virginia, it’s only a short hop to the west before I’m enjoying the scenic country highways of the Loudoun Valley and the Shenandoah foothills beyond.

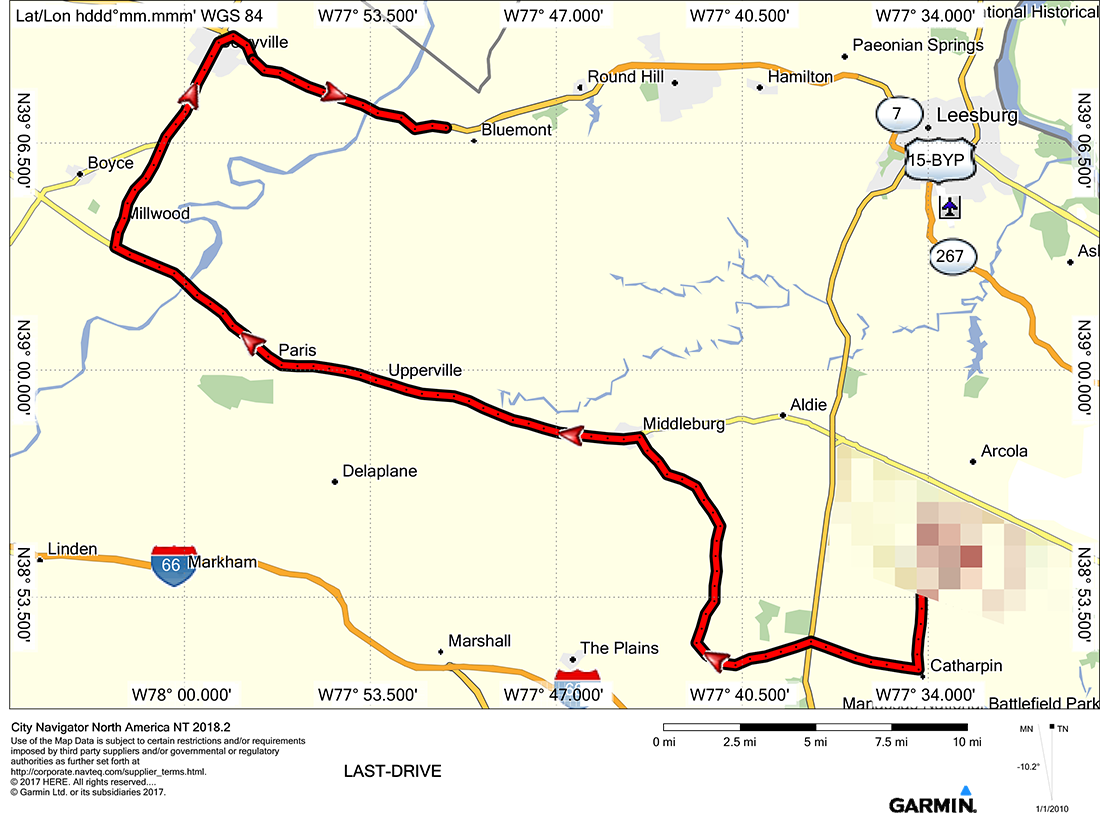

On that fateful day, I started out in my venerable 2008 Subaru Outback 2.5i at about 7:45 p.m. I headed south into Prince William County and then west toward the Bull Run Mountains that form the border between the counties of Prince William and Faquier. After traversing some twisty paved and unpaved roads, I crossed back into Loudoun County at Middleburg. I turned west on U.S. 50 and proceeded out across the valley, passing through Upperville and Paris. I climbed the Ashby Gap south of Mount Weather and crossed into Clarke County, then coasted down into the northern Shenandoah Valley and across its namesake river. Then I headed north on Virginia Route 255 through Millwood, met U.S. 340 at Briggs, and proceeded to Berryville, the county seat of Clarke.

When I arrived in Berryville, it was about 9 p.m., so I decided to start heading back home. My plan was to hop on Virginia Route 7 east, then turn right onto the historic Snickersville Turnpike (Virginia Route 734) at its northern terminus in Bluemont. The turnpike would take me diagonally across the Loudoun Valley and back to U.S. 50 in Aldie, and from there it’s just a short drive east to South Riding.

Things did not go as planned. My drive ended on the shoulder of Route 7 at Snickers Gap.

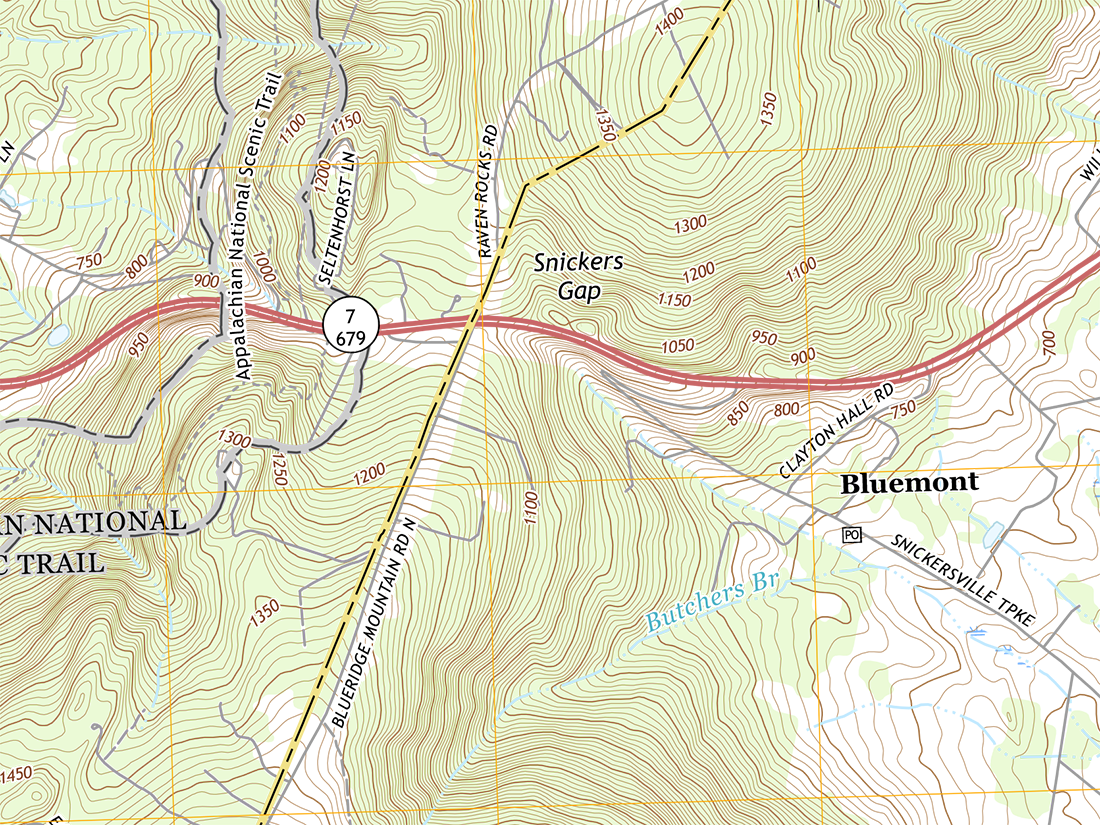

Heading east out of Berryville, Route 7—a Virginia primary state highway—is a four-lane divided highway with a speed limit of fifty-five miles-per-hour. It proceeds through the Shenandoah Valley, crosses the Shenandoah River, and then begins a steep climb toward Snickers Gap, which lies on the border between the counties of Clarke and Loudoun. From the river to the gap, over a distance of about two and a half miles, the highway gains about 200 meters (over 700 feet) in elevation.

I had my cruise control set at sixty miles-per-hour, which is a fair compromise between the speed limit (fifty-five) and the actual highest safe speed (sixty-five or seventy). The Outback’s little 2.5 liter ‘boxer’ four-cylinder engine is competent, but not exactly powerful, and so the cruise control had it revving fairly high to maintain its speed as I started up the incline. Nothing was out of the ordinary. I was well over an hour into my drive, and the car behaved as it had on countless other drives before.

And then, maybe a third of the way up the incline, the cruise control disengaged. The revs dropped to idle. The ‘check engine’ light came on.

Because I was pointed up a steep hill, the car began to slow rapidly . . . so my first instinct was to get on the gas and maintain my speed. After all, the ‘check engine’ light (which, on the Outback, always disables the cruise control) usually isn’t a big problem. It often just means that an emissions component or sensor has failed. The last time the Outback had thrown one, it was because one of the catalytic converters was failing. It did need to be fixed, but it did not prevent me from driving it in the mean time.

So I applied some gas . . . and that’s when I knew for sure that something was very wrong with the car.

First, there was the sound. At idle it sounded okay, at least as far as I could tell amid the road and wind noise, but pressing the accelerator resulted in a strange, troubling knocking sound that increased in speed (and volume) as I increased the revs. And second, when I did apply some gas, it didn’t seem to be giving me the kind of power that I’d come to expect after 132,000 miles behind this car’s wheel.

I’m not a mechanic. I didn’t have the knowledge or skill to diagnose the problem on the spot. But I knew enough to know that this was not some minor emissions problem. Whatever this problem was, it was somewhere in the heart of the engine.

What I did next is something that I can’t really explain. I probably should have pulled over to the shoulder immediately, but I didn’t. I activated my hazard lights and pressed on. For some reason, I felt like I needed to make it the rest of the way up the hill. Maybe some rational corner of my subconscious brain thought it would be safest to get to the Appalachian Trail parking lot at Snickers Gap. Or maybe, in some less rational corner of my subconscious brain, I knew that the car was dying, and it didn’t feel right to let die anywhere other than at the top of the hill.

Using the accelerator as gingerly as I could, I coaxed the wounded car forward. Snickers Gap was about a mile ahead of me (and a hundred meters or more above me). My speed dwindled. Fifty, then forty-five, then forty, then thirty-five, then thirty. Other drivers passed safely in the left lane, oblivious to my Outback’s mortal struggle, blind to its last valiant, herculean efforts to make it to the top of one last hill.

Somehow, it made it.

By the time I reached the point where Route 7 passes through Snickers Gap, I did not think that the car could climb any more. It was sounding more and more sickly as it went. I abandoned the thought of pulling into the Appalachian Trail parking lot, which is connected to the highway by a steep driveway. I pulled onto the shoulder just slightly past the crest. As soon as I came to a stop, the engine died. It would not restart.

I have a ‘plus’ membership with the American Automobile Association (AAA), which includes roadside assistance with a towing range of up to 100 miles. I called them. Within about an hour, a tow truck was there, the Outback was loaded up, and we were on our way to my usual shop near my house.

The next day, the shop delivered the news that I had expected, but dreaded. The engine was suffering from the failure of one of its connecting rods. As Wikipedia helpfully informs us, “Failure of a connecting rod is one of the most common causes of catastrophic engine failure.” The engine was, essentially, dead . . . and, unless I wanted to invest in replacing it, the car was dead with it. In good working condition, the car was worth roughly $5,000. The shop quoted me more than $9,000 to replace the engine with a rebuilt, warrantied replacement.

By obtaining my own replacement engine and using a different shop, I might have been able to get the job done for about $4,000, but that would be with a non-rebuilt engine with similar miles, and so it wouldn’t guarantee a long life or higher resale value for the car. It just wasn’t worth it.

After the engine had cooled off, it would turn-over and run . . . but it would sound sick, and after warming up it would begin to stall and misbehave. That was enough to get it from the shop back to the house, a drive of only about a mile. Over the next month I cleaned it out, removed all my radio and other equipment, researched my options, and ultimately donated it to Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Arlington. It was towed away on June 21.

From there it went to Capital Auto Auction in Temple Hills, Maryland. It was listed in their inventory, but now it isn’t . . . which probably means that it has been sold. I haven’t received a sales receipt yet, so I don’t know how much money it brought in for Catholic Charities. I hope it did well. And I hope it isn’t going to a scrap yard. Somebody with time, skill, and a donor EJ-253 engine could get it back on the road in no time. It needs some body and interior repair to the places that I had lights, antennas, and radios mounted, and of course the engine swap, but that’s all it needs. Otherwise it’s in very good shape. I took good care of it.

[Update, July 19, 2017 – It sold for $1,300 and, after fees, brought in $1,111 for Catholic Charities.]

I bought the Outback new in May 2008 with 55 miles on the odometer. It was towed off to auction more than nine years later with 132,168. Aside from a handful of miles by Melissa and during service visits, they were all mine.

In 2013, when I might otherwise have traded-up to something new, I chose to keep it and start doing some of my own upgrades . . . suspension improvements, new accessory equipment, a pillar spotlight, permanent antenna mounts on the roof, an upgraded stereo with navigation, and so-on. This car was my workhorse. I drove it on narrow city streets and alleys, broad cross-country interstates, unpaved mountain roads, and everything in-between. I drove it through snow, sleet, hail, and rain. It’s seen severe thunderstorms, flash floods, and even tropical storms. It’s taken me as far south as Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and as far west as Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. It’s been loaded to the gills with stuff and piled high with boxes on the roof rack. And it has never complained. Until its final couple of miles, it just did its job, and did it well.

I had planned to keep it for ten years, but it didn’t quite make it. Most Subarus can go for at least 200,000 miles, but apparently, some small percentage of EJ-253 engines fail between 130,000 and 160,000 with rod knock the same way mine did. It’s not a huge, systemic problem, but it’s not unheard-of either. I’m one of the unlucky few. So it goes.

Technically, the Outback’s last drive was the short run from the shop back to the house. But I’m not going to remember that one. I’m going to remember its last drive through the country. I’m going to remember that hour and twenty minute, sixty-mile trek that ended prematurely on Route 7 at Snickers Gap. And I’m going to remember that, even suffering from the automotive equivalent of a heart attack, my Outback pressed on and climbed the mountain.