In 1621, the Puritan Christian pilgrims of the Plymouth Plantation (in modern-day Massachusetts) joined with their American Indian neighbors to celebrate the ‘first Thanksgiving,’ a celebration of thanks for all that God had given them.

One particular Indian named Tisquantum, or ‘Squanto,’ was a Baptized Catholic who was fluent in English. Squanto was instrumental in helping the pilgrims establish themselves in the New World and in building the close friendship between the pilgrims and the Wampanoag Indians. That friendship would result in over fifty years of peace between the European settlers—including my ancestor, William Bradford—and the American Indians of the American northeast. You can read some more of the details in my 2010 piece, On Thanksgiving.

Many of the northeast colonies continued the tradition and celebrated annual Thanksgiving holidays, but the date of the celebration differed between the different colonies. After the establishment of the United States, the New England states continued to celebrate each fall, but the holiday was largely unknown (or at least uncelebrated) in the rest of the United States.

A magazine editor named Sarah Josepha Hale had begun advocating for a national, uniform Thanksgiving holiday in the late 1840s, but the request had fallen on deaf ears in a country that was then on the brink of civil war. And of course the war and all its horrors came in 1861. Before its end in 1865, more than 625,000 Americans were dead, 412,000 were injured, and unmeasurable harm had been done to lives and property all across the United States (and the erstwhile Confederate States).

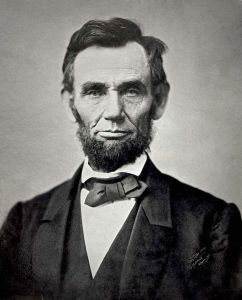

None of this stopped Hale, who wrote to President Abraham Lincoln (R) in September of 1863—more than a year and a half before the war would end—urging him to proclaim a national day of Thanksgiving anyway. She had been advocating it for fifteen years, and had written to several of Lincoln’s predecessors, but none had acted on the request. Lincoln, in the midst of the unspeakable horrors of war, thought that Hale had a good idea. He asked Secretary of State William Seward (R) to draft an appropriate proclamation, which was then issued by the President Lincoln on October 3, 1863. This proclamation, printed below (with minor modernizations of spelling and formatting), established a uniform, national Thanksgiving holiday in the United States for the first time.

In case you have any question of what this holiday is about, or what it means, read on.

The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theater of military conflict; while that theater has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the axe has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwells in the Heavens.

And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and Union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this Third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the United States the Eighty-eighth.

By the President: Abraham Lincoln