Christianity, properly practiced, is a faith rooted in both spiritual and physical things. We recognize the fundamental truth that, as human beings, we are both body and spirit, flesh and soul. These days it is trendy to attempt to divorce the two. The materialist sees the world as only matter, and rejects the notion of a soul, spirits, and even God himself. At the other extreme, many modern spiritualists (of various stripes) see matter as inherently flawed or illusory, and seek a higher plane of ‘true,’ transcendental spirituality.

But I am not merely a body, nor am I merely a soul. I am both. And as Christians, we believe that while these two elements of ourselves separate in death, they will be reunited once more at the end of time—the ‘resurrection of the body’ professed in our most ancient creeds.

Many of our beliefs reflect this body/soul duality. This is especially evident in the Sacraments, each of which are composed of physical and spiritual elements. Baptism is a spiritual seal, but is expressed with water and words. Confession is a spiritual cleansing, but we have to state our sins aloud and receive a verbal absolution. Body and soul. Flesh and spirit.

The veneration of the saints follows this same pattern. Part of the veneration of the saints is learning about their lives, following their good examples as faithful, dedicated Christians, and engaging with them through prayer. But in addition to these spiritual elements, we also have physical relics of the saints. They are not ‘good luck charms’ or false idols, but conduits through which God chooses to work in the world.

We know from Holy Scripture that God works miracles through the bodies and property of his most faithful followers. Our Jewish forebears record in 2 Kings 13:20-21 that a man was brought back to life after coming in contact with Elisha’s bones. In the New Testament era, we see in Acts 19:11-12 that the apostle Paul’s “handkerchiefs and aprons” were brought to the sick and they were healed. God works through his saints during their earthly lives, and continues to work through them even in their deaths. This was recognized in the early Christian church, which venerated martyrs and saints from the very beginning.

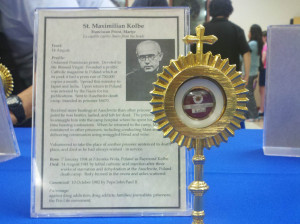

In Catholic tradition, we recognize three classes of relics. First-class relics are any items directly associated with Christ’s life (e.g., pieces of the true cross), or the physical remains of a saint (e.g., bone fragments, hair). Second-class relics are items that a saint wore or used regularly (e.g., a cloak, a crucifix, a book). A third-class relic is an object that has been touched to a first or second class relic, which makes it possible for millions of Catholics to have their own relics for private veneration and prayer. The photograph above is of a first-class relic of my own Confirmation saint, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, whose feast day happens to be today. It is a small piece of hair from his head. This relic was part of an exposition of sacred relics that visited my parish last month, and I was able to touch my own Saint Maximilian medal to it, which makes it a third-class relic.

The physical act of touching one of my belongings to a small piece of Saint Maximilian Kolbe’s body means nothing, if you are a materialist or a spiritualist. To the materialist, anything and everything Maximilian Kolbe was terminated when he died, there is no God to keep his spirit alive, and my medal underwent no discernible change. To the spiritualist, you can unite yourself directly with any spirit you wish, and physical objects would only get in the way of a true transcendental bond. But for us Catholics, recognizing that humanity is both body and soul united, the best spiritual bonds are those forged in a physical action.